Prof. Arunaditya Sahay (View Full Profile)

Dean (Research)

Professor of Strategic Management, BIMTECH

With the withdrawal of troops by the traitor Chief Minister of Tipu Sultan, Mir Sadiq, the fourth Anglo-Mysore war tilted in favour of the British Allied Army, supported by the Nizam of Hyderabad. Tipu Sultan died in action and the whole of Mysore Kingdom whose capital was Srirangapatnam came under British control on May 5, 1799.

The victory celebrations of the British army was cut short by the attack of malaria which did not affect the local population as they had developed self-immunity over the centuries. Malaria, which was caused by mosquito bite, made the British Army to shift its operations to Bangalore where quinine, which was under development, was made available to the soldiers for their treatment.

For the scientists in Europe, this was a good opportunity for getting data from human test. Thus, India came to know about quinine, it is said that quinine was used to treat malaria as early as the 1600s in Peru, where it was referred to as the “Jesuits’ bark,” “cardinal’s bark,” or “sacred bark.” Be that as it may, today India is world’s largest producer of quinine in its various forms.

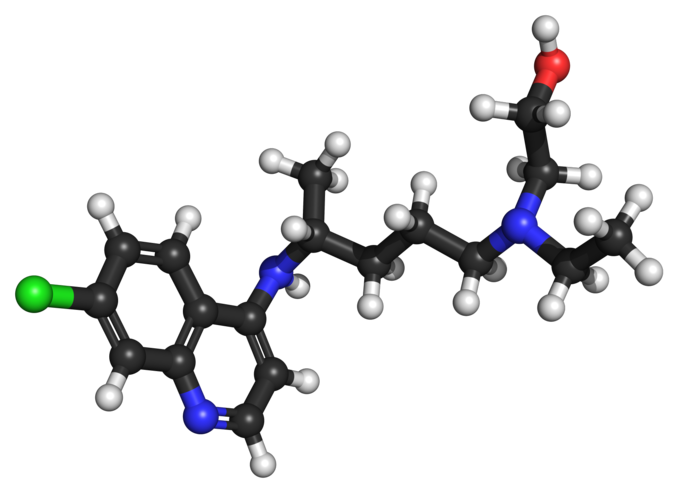

Quinine is extracted from the bark of cinchona tree; the name ‘cinchona’ was given in honour of Spanish Countess of Chinchon, who, during her stay in Peru, had contracted a fever that was cured by the bark of this tree. The bark of the tree was mainly used for the treatment of malaria, an infection caused by the protozoan parasite Plasmodium, which, in turn, is transmitted to humans by the bite of various species of mosquitoes.

Since the first application of quinine in India in 1799, almost two and a quarter century have passed but quinine, in different forms, remained the only effective remedy for malaria. Over the years, various combinations were developed and its use was widened.

In 1944, a synthetic version of quinine was developed in a laboratory but the quinine extracted from cinchona bark remained popular as the synthesized drug was then not commercially viable.

Quinine is an alkaloid that acts on human body by interfering with the growth and reproduction of the malarial parasites. These parasites inhabit the red blood cells (erythrocytes). With the administration of quinine to infected human body, the parasites disappear from the blood. However, in many cases, after the quinine treatment was over, the recovered patients were attacked again by malaria after a few weeks. As quinine was failing to provide complete cure from malaria, better drugs for malaria cure were developed during World War II.

Among them, chloroquinine and primaquinine were found to be more effective. With the advancement of technology, these antimalarials could be produced on a commercial scale by synthesis. But during the 1960s, various strains of the malarial parasite developed resistance to the synthetic drugs, more so, to chloroquine, that was highly valued then. Surprisingly, the parasite were still sensitive to traditional quinine.

This, perhaps, made WHO to recommend quinine in various parts of the world as the drug of choice despite the adverse side effects such as deafness, disturbances in vision, rash, and gastrointestinal symptoms while administering large doses over a longer time.

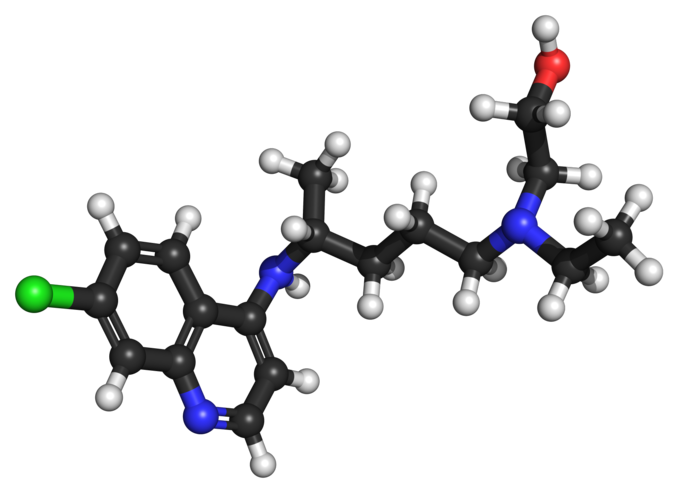

Apart from malaria, both chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) are being currently used in the treatment of rheumatic diseases, skin diseases and in chronic Q fever. During the past few decades, these drugs have been recognized also as a potential antiviral agent.

Currently, it is being used for possible treatment for the acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) which is believed to cause Covid19. Earlier, some reports from China had found that chloroquine could inhibit SARS-CoV-2 in vitro. Further, it showed some efficacy in treating Covid19. A small trial in France, which was non-randomised, had shown hydroxychloroquine to have a potential for treatment.

Perhaps, these findings have prompted US President Donald Trump, to tout hydroxychloroquine as a game-changer in the fight against Covid19. The US Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has designated hydroxychloroquine for off-label, compassionate use for treating Covid19.

Even the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) recommended HCQ for preventive medication in high-risk Covid19 patients. WHO, on its part, has added the drug for trial with a variety of ailments. But virologists and infectious disease experts are cautioning its use as they consider it to be premature though Trump stated it to be “one of the biggest game changer in the history of medicine.” He went to the extent of warning India for non-supply of hydroxychloroquine.

The government of India, wanting to help countries suffering from Covid19, has partially lifted the export ban. India could do so as the manufacturers within the country produce 70% of the world’s supply of HCQ.

Trump’s threat of “retaliation,” thus, became infructuous as the U.S. order of 29 million doses of HCQ was despatched. Meanwhile, the two leading manufacturers, namely Zydus Cadila and Ipca Labs ramped up their capacity.

Within no time, the share of these companies rose by 40% and 29% espectively. Zydus Cadila has increased their production of HCQ from 3 metric tons/month to 20 to 30 metric tons/month which can be, based on the requirement, increased to 50 metric tons. Ipca Labs, which has HCQ capacity of 20 tons can increase their manufacturing capacity to 30 metric tons/month within a month.

With the increased HCQ manufacturing, the packing and labelling lines have to simultaneously increase their capacity. The good news is that both these pharma companies have the necessary raw materials and key starting ingredients. The world, therefore, need not worry about supplies of HCQ which is ruling the roost.

#Covid19 #Coronavirus #Coronavaccine #Hydroxychloroquine #HCQ